Last year saw a widespread sharp rise in commodity prices, and the rally in copper and iron ore extended into the early part of this year, helped by surging oil prices. Correlations between financial markets and commodities have also risen to very high levels. With massive amounts of fiscal and monetary stimulus in the pipeline, some have assumed that this is the start of the next commodities supercycle.

While there are good reasons to think that demand will boom this year, we expect these assumptions to prove misplaced.

China’s rapid urbanisation drove the previous boom

Before I explain why we do not expect a widespread commodities supercycle, it is worth looking back at the last supercycle to examine what happened, why it occurred, and where we are in relative terms.

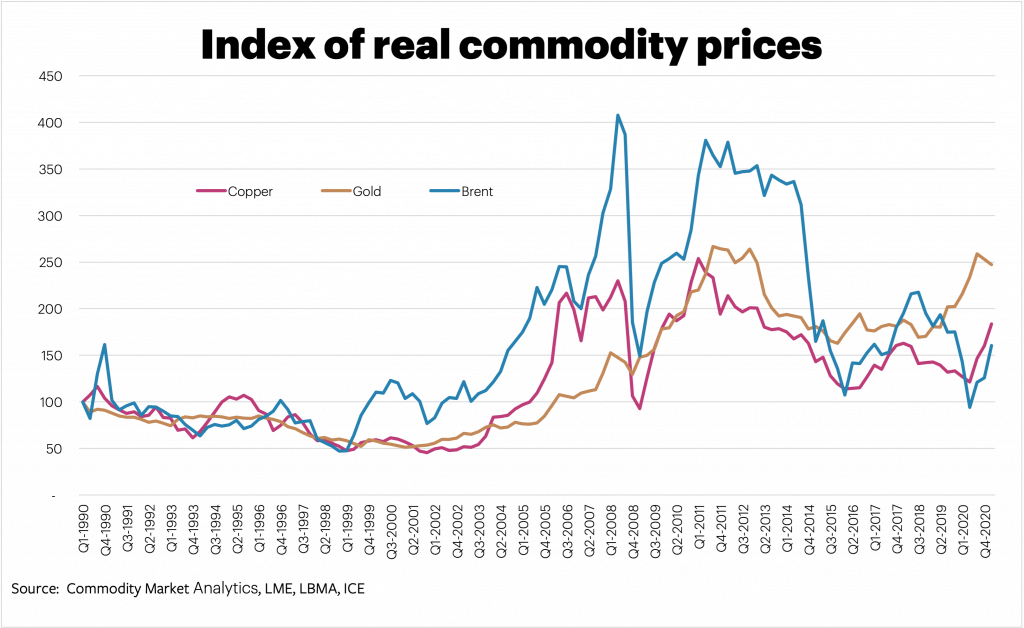

In this first chart, we show an index of prices for copper, gold and oil. Prices are adjusted for inflation and are shown in real terms.

Prices for many commodities started to pick-up from 2001, when China began its rapid industrialisation and urbanisation, with the country opening up to the West and joining the WTO in that year.

China rose from a low base, so it took a few years for the global extraction industry to feel a material difference. However, from 2004 prices of copper, oil and other commodities started to surge, catching most producers off guard after years of steady demand growth and low prices. Once prices began to rise rapidly, investors and speculators soon leapt on the bullish bandwagon. This added to the fierce upward momentum. Copper and gold rose by more than five times from 2004 to 2011, with oil seeing a sevenfold increase at its peak.

The supercycle started to breakdown in 2011, as the market rebalanced

Eventually, the tide started to turn as high prices damaged demand and supply adjusted to the new reality. Copper prices began to fall in 2011; gold and oil prices dropped soon after. The China demand boom was undoubtedly a bolt from the blue, and it took around seven years for supply and demand to realign fully.

In terms of the most recent trend in prices, we can see that copper, gold and oil prices have been rising together in late 2020 and early 2021, showing that cross-commodity correlations are rising.

These trends suggest a new supercycle may be starting. However, gold prices already look high. They reached a peak in Q4 2020, similar to the one back in 2011, and prices have fallen significantly since then.

Copper and oil prices still look low in real terms, although this does not mean that they are both going to jump from here for the reasons discussed below.

The green energy revolution looks set to accelerate demand for metals

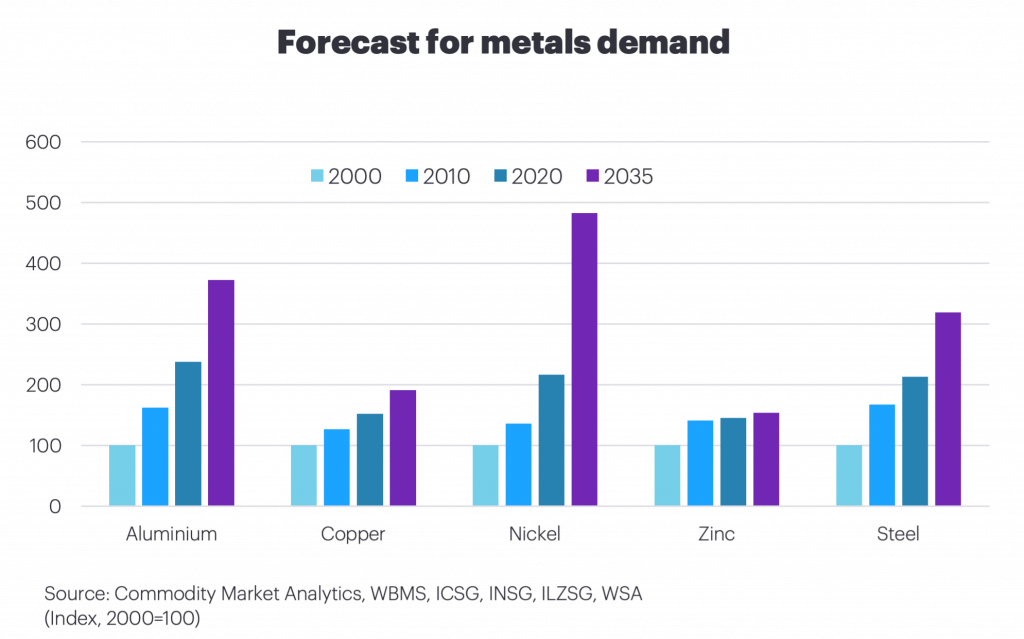

The chart below shows how we expect demand to change by 2035 if historical trends in intensity of use remain the same as they were in the five years from 2015 to 2019.

This analysis is a helpful starting point for thinking about whether another supercycle is imminent. We expect to see significant demand growth in markets like aluminium, nickel and steel, which could exert upward pressure on prices.

We believe, however, that copper has the greatest potential to spring a positive demand shock. The industry is primed for a period of slow growth (as we have seen recently). But as the green energy revolution gathers momentum, the amount of copper consumed in electric vehicles (EVs) and the power grid is likely to rise sharply.

EVs contain three to four times as much copper as a traditional vehicle. Car sales in China rose by a modest 2% last year, but sales of New Energy Vehicles rose by 11%

Other metal markets will also face upward pressure on demand, which will challenge producers to respond. Aluminium is likely to be boosted by the greater use of solar panels. Nickel is also used widely across a range of clean energy technologies. Cobalt and lithium are also favoured materials for the early generations of high-performance automotive batteries.

Oil faces a negative demand shock, so a commodities supercycle looks far-fetched

On the other hand, oil faces a negative demand shock. EVs mean a switch away from gasoline – a key consuming area for oil – and this could easily result in oil demand underperforming the baseline that the industry has planned for and been comfortable with.

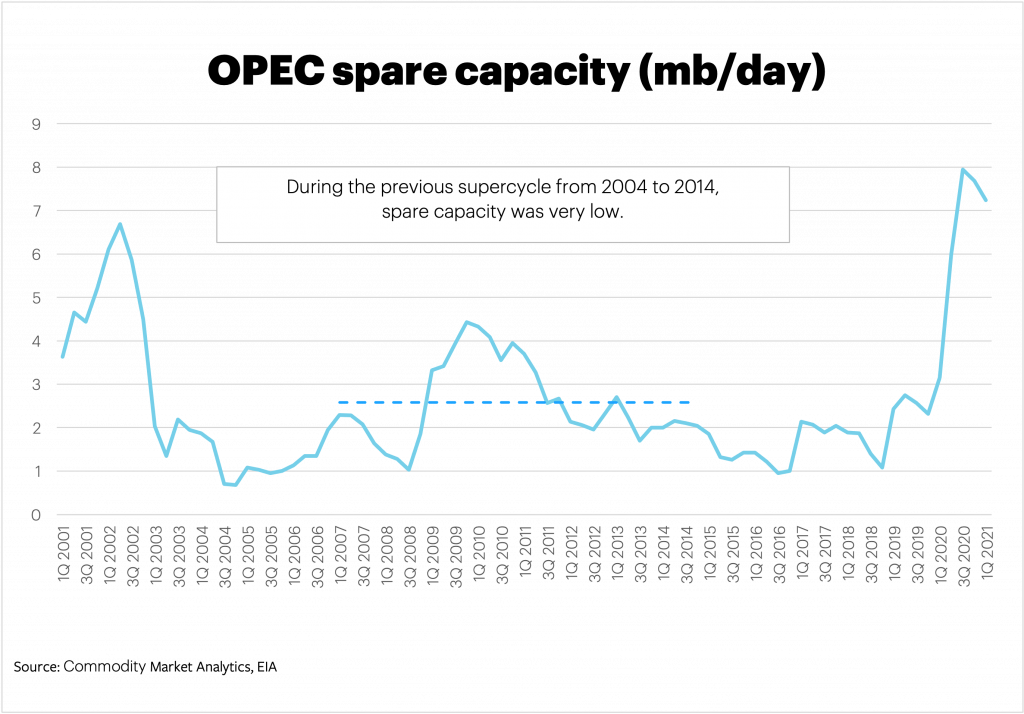

Supply-side dynamics will also help determine whether the recent rise in commodity prices will accelerate over the next few years. In particular, can producers cope if demand starts to surge unexpectedly?

For oil, we expect the supply adjustment to be rapid, severely limiting the potential for price rallies to last for any length of time. First, OPEC spare capacity is very high indeed.

The recent rally in oil has been based on strong control by the OPEC+ group, which has helped to underpin prices.

The problem is that OPEC recognises that inflated prices will damage demand and encourage price-sensitive producers to return to the market. These consequences could lead to another damaging fight for market share.

The cartel, therefore, has a strong incentive to minimise the chances of a price spike and spare capacity means it has ample ammunition in reserve should it need it. On top of this, Iran has been hampered by US sanctions. Production could easily rise from today’s depressed level, making life more difficult for the rest of OPEC.

Higher oil supply could also come from US producers

Furthermore, US producers are waiting in the wings for high prices to signal that investment in the tight oil sector should accelerate, which would lead to increased drilling and production further down the road.

The past five years have seen investors in tight oil suffering from losses and bankruptcies, making them far more cautious. But persistent high oil prices would quickly alter this mindset. Again, this reinforces the idea that high oil prices would only be a short-lived phenomenon at best.

Given the supply-side challenges, we see the chances of an imminent supercycle in oil as being very low indeed, with important implications for other commodities.

Oil is a special part of the story because high oil prices feed through higher production costs of other commodities, such as aluminium, copper, and steel. If oil prices are stable or fall, the chances of a jump in other markets are reduced, leaving demand as the key driver of commodity prices rather than supply and the costs of production.

Supply-side dynamics will determine the breadth of any commodities supercycle.

In conclusion, the evidence for another widespread supercycle is mixed. Prices for copper and oil have both jumped this year. Still, gold prices have fallen, suggesting that individual fundamentals will play a more important role this year, rather than the broader liquidity wave coming through from central banks and governments.

In terms of mining employment, the landscape seems to be changing. Mining has traditionally been seen as an enemy of environmentalists, but the green energy revolution will require a change in this mindset. The expansion of mining in areas that support clean energy generation and storage will be vital to enable the move away from fossil fuels.

In terms of demand, we see significant upside risks for aluminium, copper, nickel and steel, but oil is facing the prospect of losing market share in key areas. Supply-side dynamics will also be crucial as commodity producers respond if they can to price incentives.

The industrial metals look set for a selective supercycle, but bullishness in oil looks like a mirage of hope over reality.

Dan Smith, Director – Special Projects

Read more of Dan Smith’s blogs analysing commodity markets.

Image (c) Shutterstock | Vintage Tone