Economic woes ease, but poor situation remains

Economic activity picked up in September, as workers returned from summer holidays. The seasonal return, though, was sluggish, and the lift slight in comparison to typical Septembers. The fears for the economy are that underlying weaknesses and risks weakness persists and that the seasonal uptick is not enough to overcome the drags on the economy.

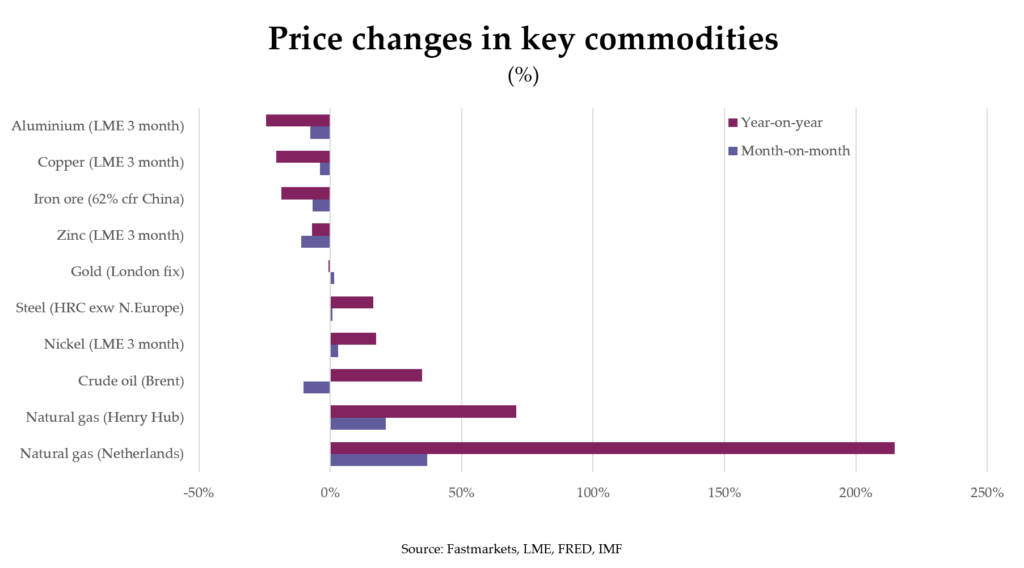

The clearest sign of the underlying problems is in commodity prices.

Most have fallen again – welcome news for consumers, but a sign of slackening demand. The leading base metals, copper and aluminium, are now below the levels they were in September 2021, when the pandemic was still sapping the economy. And most agricultural products are returning to previous years’ levels.

The main commodity of concern that defies the downward price pressure is still gas. With fears that stocks in Europe will be depleted over the winter, prices have risen for another month.

Weaker demand depresses most commodities

The poor economic picture is depressing demand and deflating the prices of most commodities. This is true of both metals and agricultural commodities, and even crude oil is now below $100/barrel. The falling oil price has concerned OPEC+ members enough, that they voted to reduce crude oil production to stop prices from falling. Quotas have been decreased by two million barrels per day, or about 2% of global production.

Aluminium is being affected by both costs and demand. Not only is demand falling, but a third of the cost of production of aluminium is energy, so aluminium plants that use petrochemical-generated electricity are seeing profitability squeezed. Indeed the two largest producers in the United States, Alcoa and Century Aluminium, both attributed weaker earnings or layoffs to the high energy costs.

The Ukraine-Russia conflict continues to affect global economies negatively. A ratcheting up of rhetoric and the annexing of four territories by Russia offer little hope that an end to the war is near. If anything, further hostilities are likely. So, gas and other affected commodities are unlikely to see any sharp correction in prices.

Inflation stabilises, though yet to peak

The drops in the prices of steel, oil and agricultural products, especially, have helped stem the rise in inflation. In the US, inflation actually came off slightly, while rises in other geographies have decelerated.

However, analysts and central banks caution that further rises are inevitable. Some businesses have been trying to shield customers from some of the price rises for fear of losing business. With prices staying high for so long, costs cannot be adsorbed and are increasingly being passed on in full, meaning more price rises and by a greater amount. Coupled with gas prices appreciating, and so electricity to a lesser extent, ahead of winter, inflation will lift again through to the start of the next year – though forecasts for peak values have been massaged down.

Consumers counting the cost

Consumer confidence has not improved. Lower disposable income and concern about future prospects have all eroded the previously expected post-pandemic upswing. Now, savings build up during previous years are also dwindling, leaving little latitude for households to increase their spending. This can be seen in the start of an upswing in rates of consumer credit.

A positive, and partly counter-intuitive indicator, is the ongoing strength in the labour market.

Unemployment is unusually low. In six of the G7 countries, unemployment is at or close to the lowest level of the last 20 years. Companies are reporting difficulty in securing workers, with some having to accept lost production. Low unemployment can be attributed to workers not returning to the workforce after the pandemic or not being able to travel as easily to where they’re needed.

Despite the low unemployment, wage rises are being hotly contested and held low in comparison to the worsening economic picture. The effective wage cuts are seeing groups of workers in several countries striking for greater increases.

Europe a prisoner to gas storage

European countries have been working to fill storage. The loss of Russian gas supplies, with the Nord Stream 1 gas pipeline first stopped for technical reasons and lately damaged by several explosions, Russian flows have stepped down noticeably.

LNG is being sourced from other territories, but the question persists, “Will there be enough gas for the winter?” The OECD thinks not, unless demand is reduced.

On the assumption that demand will match the average of the last 5-years’ consumption and that additional gas will be sourced only from Norway and the UK, the OECD forecasts that gas storage levels would fall below the level likely to cause supply disruptions by February 2023. Worse still, if the winter is cold, so that gas demand reaches the maximum levels used over the last five years, then problems are likely from January and storage is depleted by March.

Only if demand is reduced, by around 10%, can Europe be expected to avoid supply issues this winter. This is likely, as the EU has agreed a voluntary plan for each country to reduce demand by 10% between December and March 2023. This is coupled with a mandatory plan for a 5% reduction during peak hours.

Gloomy outlook for economic growth

Inflation is yet to peak and will be a sustained drag on sentiment and economic growth.

Such high levels of inflation are partly to blame for the World Economic Forum (WEF) downgrading GDP growth forecasts again in their September update, entitled “Paying the Price of War”. The WEF is not alone in scaling back on its growth expectations.

With several broad questions persisting, the next months will be telling for global economies:

- Can Europe effectively manage gas availability and storage over the colder months?

- How will China overcome the economic drag of its construction woes and “zero-Covid” policies?

- How will the next phase of the Ukraine-Russian conflict develop?

As the answers to these questions become clearer, they will indicate the strength of economic growth in 2023 and onwards, and so enable governments to gauge the level of response. Until then, businesses concerned about the future, waning consumer confidence and high inflation levels will slow economic improvement and could feed into a self-fulfilling negative cycle.

Jason Kaplan

Director (Special Projects)

Jason Kaplan has been analysing commodity markets and forecasting developments for more than 20 years. He combines a keen understanding of commodities, the commercial drivers of companies along the supply chain, and the effects of macroeconomic factors to predict how markets will develop.